The time of the Greco-Persian wars occurred. War of ancient Greece with Persia

Greco-Persian Wars

In the second half of the 6th century. BC e. Persia turned into a powerful slave state. Having conquered Phenicia, Palestine, Babylonia, Egypt and all of Asia Minor, she considered the conquest of Greece .

|

Greco-Persian wars (5th century BC). |

Persia was quite a formidable opponent. Its army, consisting mainly of residents of conquered countries, outnumbered the Greek one. But Persian infantry was still significantly weaker than the Greek one. She did not have that moral unity that distinguished Greek troops .

Persia did not have its own ships, and its fleet consisted of ships from conquered states, including Phenicia, Egypt, and Greek cities in Asia Minor.

The Greeks had a very small fleet before the start of the war.

The wars of Greece with Persia were wars of a young slave-owning military democracy, which was based on a more developed slave-owning mode of production, against the state, based on the system domestic slavery . The Greeks fought in these wars for their independence, and this strengthened their moral unity. The Persians did not and could not have such moral unity, since they led wars of conquest .

The first campaign of the Persians.

The reason for the war was the assistance provided by Athens and Eritrea to the Greeks of Asia Minor who rebelled against the Persian yoke. In 492 BC. e. Persian troops under the command of Mardonius, son-in-law of the Persian king Darius , from Asia Minor crossed the Hellespont (Dardanelles) to the Balkan Peninsula and headed along the northern shore of the Aegean Sea to Greece. The fleet also took part in this Persian campaign against Greece.

A feature of the joint actions of the army and navy in the first campaign of the Persians was the use of the fleet, which accompanied the army along the coast to supply it with food, equipment and to secure its flank.

Near Cape Athos during a storm, a significant part of the Persian fleet was lost, and the army suffered heavy losses in clashes with the Thracians. Given the almost complete absence of land roads in Greece suitable for the movement of a large army, and the lack of local food resources to feed the troops, the Persian command considered it impossible to achieve the goal of the war with ground forces alone. Therefore, the campaign against Greece was interrupted and the Persian army returned back to Persia.

Second campaign of the Persians.

Marathon battle.

In 490 BC. e. The Persians launched a second campaign against Greece. The navy also took part in it. But the method of joint action between the army and navy was different in this campaign. Persian fleet now transported a land army across the Aegean Sea and landed it on Greek territory near Marathon. The Persians chose the landing site well. Marathon was only 40 km from Athens.

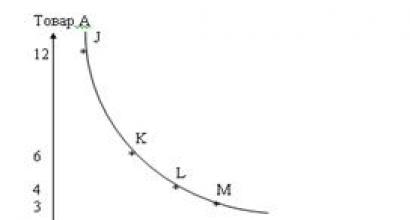

The Persians had 10 thousand irregular cavalry and a large number of foot archers. The Greeks had 11 thousand hoplites. The Athenian army was commanded by 10 strategists, among whom was Miltiades, who knew the Persian army well. Some of the strategists, seeing numerical superiority Persians, proposed to retreat to Athens and there, under the protection of the city walls, wait for the enemy. But Miltiades insisted on giving battle. Greek phalanx was built by him at the entrance to the Marathon Valley. To paralyze the flank attack of the Persian cavalry, Miltiades, by weakening the center of the phalanx, strengthened its flanks, increasing the number of ranks here. In addition, the flanks were covered with abatis.

Unable to use cavalry on the flanks, the Persians placed them in the center of their battle formation.

The Persians began the attack. They showered clouds of arrows on the Athenian hoplites. To reduce the losses of his troops, Miltiades gave the command to begin moving the phalanx forward. The phalangists went from walking to running. In the ensuing battle, the center of the Greek phalanx was broken through. But on the flanks the Greeks won and put the enemy to flight. Then the Greek flanks attacked the part of the Persian army that had broken through in the center and defeated it.

Despite the numerical superiority of the Persians, the Greeks won on the Marathon Plain. The army with better organization and discipline, with more advanced tactics, won.

However, the Greeks, due to the slowness of the phalanx and the absence of a fleet in the Marathon area, were unable to develop the success achieved. The Persian troops who fled from the battlefield managed to board ships and went to sea without interference. The Greeks captured only seven enemy ships.

The Battle of Marathon, which took place in September 490 BC. e., is an example of the reflection of a landing force.

Third campaign of the Persians.

Despite the failure of two campaigns, the Persians did not want to give up their intention to capture Greece. In 480 BC. e. they organized a third campaign.

The ten-year period between the second and third campaigns was characterized in Greece by a fierce struggle on issues of preparation and conduct of war.

Two political factions fought. The first of them, consisting of slave owners associated with trade and craft, the so-called "sea party" led by Themistocles , insisted on building a strong fleet. The second group, which included slave owners associated with agriculture, and was led by Aristide, believed that for a future war the fleet was not important and that it was necessary to increase the ground forces. After a tense struggle in 483 BC. e. Themistocles' group won.

By the time of the new Persian attack, the Athenians had a strong navy, who played an exceptional role in the hostilities that then unfolded.

In 481 BC. e. thirty-one Greek states, on the initiative of Athens and Sparta, in order to unite the forces of Greece to fight the Persians, created military defense alliance . This increased the advantages of the Greeks in the upcoming struggle.

The Greek war plan boiled down to the following. Due to the fact that Persia had a numerical superiority in forces, it was decided not to fight in the open field, but to defend the mountain passes. During defense by the army Thermopylae Gorge the fleet was supposed to be located at Cape Artemisium (the northern tip of the island of Euboea) and prevent landings in the rear of the ground forces.

Thus, The Greek plan provided for simultaneous and coordinated actions of the army and navy.

According to the Persian war plan, their troops were to cross the Hellespont, move along the coast of the Aegean Sea and, having defeated the Greek ground forces, occupy the territory of Greece.

The Persians thought of using the fleet according to the type of the first campaign. He was supposed to go along the coast, parallel to the movement of the army, and, destroying the Greek fleet, “carry out the following tasks:

- supply the army with everything necessary;

- by landing troops in the rear of the Greek army to promote the advancement of their army;

- protect the flank and rear of your army from the influence of the enemy fleet.

To avoid a detour around Cape Athos, near which most of the Persian fleet perished during the first campaign, a canal was dug in the narrow part of the Akte Peninsula.

The armed forces of the Persians in the third campaign against Greece were led by King Xerxes himself.

The Persian army still had many warriors from conquered countries who were not interested in the victory of their enslavers. The Persian fleet also consisted of ships from various states conquered by Persia. This circumstance, as in the first two campaigns, was one of the reasons for the low morale of the Persian armed forces.

To protect the Thermopylae Gorge the Greeks concentrated a small detachment of hoplites under the command of the Spartan king Leonidas . A united Greek fleet consisting of 270 triremes, of which 127 belonged to Athens, was sent to Cape Artemisium. The task of the fleet was to prevent the advance of the Persian fleet into the area of Thermopylae and thereby deprive it of the opportunity to provide support to its army. At the head of the Greek fleet was the Spartan navarch Eurybiades, but the actual command was in the hands of the head of the Athenian detachment, Themistocles. The Persian fleet consisted of approximately 800 ships.

Under such conditions, the battle was unprofitable for the Greek fleet. And Themistocles, having correctly assessed the situation, took with his ships at Cape Artemisium a position that blocked the Persians’ passage to Thermopylae and at the same time did not allow them to deploy all their forces for battle and thereby use their numerical superiority. After this, the Greek fleet, without getting involved in lengthy military clashes with the enemy, before darkness fell, launched a series of rapid strikes against part of the forces of the Persian fleet, thereby depriving it of the opportunity to assist its army during the battles at Thermopylae.

Thus, the Greek fleet, by occupying an advantageous position and active actions at Cape Artemisium, provided significant assistance to its army fighting at Thermopylae. The successful actions of the Greek fleet raised the morale of its personnel and showed that the Persian fleet could be defeated, despite its numerical superiority.

When it became known about the fall of Thermopylae, the presence of the Greek fleet at Artemisium lost its meaning, and it, moving south, concentrated in the Strait of Salamis.

The Persian army, having passed Thermopylae, invaded Central Greece and occupied Athens. The Persian fleet concentrated in Phaleron Bay,

Disagreements arose among the Greeks about the further use of the fleet. The Spartans sought to retreat to the Isthmus of Corinth, where the fleet, together with the army, was supposed to prevent the Persians from invading the Peloponnese. Themistocles, who led the Athenians, insisted on giving battle to the Persian fleet, using a tactical position in the Strait of Salamis advantageous for the Greek fleet. The small size of the strait did not give the Persians the opportunity to deploy their entire fleet and thereby use their numerical superiority.

Meanwhile, Xerxes, deciding to give battle to the Greek fleet, closed the exits from the Strait of Salamis with his ships.

The Greeks, at the insistence of Themistocles, decided to take the fight.

Salamis fight

The Battle of Salamis took place at the end of September 480 BC. e. The Greek fleet, which consisted of about 350 triremes, was deployed in a double front formation along the coast of the island of Salamis. Both flanks rested on the coastal shallows, which guaranteed them from being bypassed by Persian ships.

The Persian fleet, numbering approximately 800 ships, began to enter the Strait of Salamis the night before the battle.

The formation of the Persian fleet took place all night. The rowers were tired and did not have time to rest, which could not but affect the course of the battle.

The Persians took up a position against the Greek fleet, on the opposite shore of the Strait of Salamis. In an effort to deploy as many forces as possible, they formed their ships in three lines at close intervals. This did not strengthen, but weakened the battle formation of the Persian fleet. The Persian ships that did not fit into the line were placed in the eastern passages to the Strait of Salamis.

The battle began the next morning. The Athenian triremes, located on the left flank of the Greek fleet, quickly attacked the right flank of the Persians, where the Phoenician ships were located. The cramped position of the Persian fleet made it difficult for its ships to maneuver. The crowding increased even more when the ships of the second and third lines of the Persians, wanting to take part in the battle, tried to take a place in the first line. One of the Athenian triremes rammed an enemy ship on which Xerxes' brother, Ariomenes, was located. The latter, trying with a detachment of soldiers to go to the Greek trireme and on its deck to decide the outcome of the duel in his favor, was killed.

The successful attack of the Athenians and the death of Ariomenes upset the Persian right flank. The ships of this flank, trying to get out of the battle, began to move towards the exit from the Strait of Salamis. This brought chaos to the center of the Persian fleet, which had previously withstood the onslaught of the Greeks; The left flank of the Persians soon fell into disarray.

The Greeks, inspired by their success, intensified their attack. Their triremes broke the oars of the Persian ships, rammed them and boarded them. Soon the entire Persian fleet, under the pressure of the Greeks, fell into complete confusion and rushed in disarray towards the exit from the Strait of Salamis. The slow-moving ships of the Persians, located crowded together, interfered with each other, collided with each other, and broke their oars. The battle ended with the defeat of the Persian fleet. The Persians lost 200 ships, the Greeks - only 40 triremes.

Conclusions. The main reason for the victory of the Greeks was that the organization of their fleet, its combat training, the quality of ships, and tactical art were higher than that of the Persians.

The victory of the Greeks was also due to the fact that they fought a war for their independence and were united in their desire for victory, therefore their fighting spirit was incomparably higher than that of the Persians.

The victory of the Greeks was facilitated by the correct choice of position for battle in a narrow area, where they could deploy all their forces, rest their flanks on the banks and thereby protect them from being outflanked by the enemy, while the Persians were deprived of the opportunity to use their numerical superiority.

An important role in the outcome of the battle in favor of the Greeks was also played by the fact that the personnel of the Persian fleet were tired from the night formation, while the personnel of the Greek fleet rested all night before the battle.

The main tactical method of battle was the ramming attack, supplemented by boarding.

The Salamis battle had three phases: the first phase consisted of building the fleet and occupying the starting position at the chosen position, the second - in the rapprochement of the opponents, and the third - in the actual collision of individual enemy ships, when the matter was decided by ramming and boarding.

Control of forces in the hands of the command remained only in the first two phases. In the third phase, control almost ceased, and the outcome of the battle was decided by the actions of single ships. The commander in this phase could influence in a certain way only by personal example.

|

|

Played a major role in organizing the victory Themistocles. He was the first to understand the need for a fleet as an integral element of the armed forces. An outstanding naval commander, he knew how to correctly assess the situation and, in accordance with it, set specific and realistic tasks for the fleet.

The Salamis victory of the Greeks was a turning point in the Greco-Persian wars. The defeat of the Persian fleet deprived their army of sea communications. Land communications were so stretched that they could not supply the large Persian army. As a result of this, Xerxes retreated to Asia, leaving a small force in Greece under the command of his relative Mardonius.

The next year, 479 BC. e. hostilities resumed. In the battle of Plataea (in Boeotia), the Greeks defeated the troops of Mardonius. In the same 479, the Greek fleet defeated the Persian fleet near Cape Mycale (the western coast of Asia Minor). Thanks to these victories, the Greeks were able to expel the Persians from Greece, from the islands of the Aegean archipelago and from the western shores of Asia Minor and thereby defend their independence.

The Greco-Persian Wars were won by more advanced, better organized and better trained armed forces.

The victory of the Greeks in the wars with the Persians was a victory of a new, higher system ancient slavery above the system domestic slavery .

The victory of the Greeks over the Persians was of great importance for the further development of Greece. She contributed to economic, political and cultural development Greek states"especially Athens, which captured enormous booty and prisoners.

Greece is known to everyone as one of the most developed ancient states. Its inhabitants had to participate in many conflicts with other empires, but the largest among them are considered to be Greco-Persian wars described by Herodotus in his work “History”. What caused the clash between the two strongest powers of that time? How did events develop? All this and much more interesting facts you can find out right now!

Greco-Persian Wars. 499-493 BC e. Ionian revolt

Photo: obm.interfile.site.ruOne of the most common reasons wars are the uprising of oppressed peoples dissatisfied with their situation: high taxes and neglect by the rulers of the empire force ordinary citizens to rebel. They are often supported by all kinds of military units and senior officials.

But the Greco-Persian wars did not simply begin because of an uprising by disgruntled citizens. Here the rulers had a hand, or as they were called at that time - tyrants, who were in fact Persian henchmen. First of all, this is the current head of Miletus - Aristagoras, who quarreled with the closest associates of the Persian Emperor Darius during the unsuccessful campaign against Naxos. Hestia, his cousin, who was in “honorable imprisonment” in the ruler’s palace, also contributed.

Aristagoras feared that the failed campaign would significantly affect his position. The tyrant gathers a military council, where a decision is made to start an uprising against the rule of the Persians. The seeds of war fell into fertile soil: the Ionian Greeks had long been dissatisfied with the huge taxes. The fact that he resigned as a tyrant and proclaimed Miletus a democratic republic also played in Aristogora's favor.

The leader of the rebels was not stupid: he understood that without allies his cause was doomed to failure. In search of comrades-in-arms, he goes to Greece. In Sparta, he receives a categorical refusal: King Cleomenes could not be won over to his side either by bribery or by the promise of rich profit. But the Athenians and Erythrians decided to help the rebels and allocated 25 ships.

Photo: otvet.mail.ru

Photo: otvet.mail.ru So, the Greco-Persian wars began with the destruction of the richest city in Persia - Sardis. Darius' troops, at that moment moving at full speed towards Miletus, were forced to change the direction of the offensive. There were no more rebels in Sardis, but imperial army managed to overtake them near nearby Ephesus. In the ensuing battle, the rebels suffered a crushing defeat and lost a strategically important ally: the Athenians left the camp and went home. But Darius harbored a grudge against them, which largely became the reason for the continuation of the Greco-Persian wars.

Rebellions against imperial power broke out like wildfire in one city after another. But the Persians were inexorable: successively conquering Cyprus, Propontis, Hellespont, Caria and, finally, Ionia, they brutally dealt with the rebels and eliminated all sources of discontent. Miletus was the last to fall in the Battle of Lada, where, in fact, thoughts about liberation from the oppression of the emperor came from. But this event did not mark the end of the war. Vice versa. The most interesting things were just beginning...

Greco-Persian Wars. 492-490 BC e. Campaigns of Darius I

Photo: pinme.ru

Photo: pinme.ru The Persian emperor was never able to forgive the Greeks for their participation in the Ionian uprising. The time has come for the inhabitants of the city-policies to defend their freedom - in 492, the army of Darius I crossed the borders of Persia and headed towards Hellas.

The first campaign was more of an expeditionary nature: the king wanted to know the strengths and weaknesses of his enemy. Nevertheless, it was not without the capture and destruction of cities: the Persian army, commanded by Darius’s comrade-in-arms Mardonius, conquered 13 Greek city-states, including Enos and Mirkin. He managed to capture Thrace and Macedonia, forcing Alexander the Great into an alliance with the Persians, but after an attack on the island of Thassos, the commander’s luck turned away: the fleet at Cape Athos was overtaken by a storm, as if Poseidon himself, heeding the prayers of the Greeks, sent misfortune to their opponents. The land army was defeated by the Brigs, a warlike tribe living in the area.

Mardonius himself was wounded in battle and fell out of favor. The king of the Persians, having made up for his losses, again gathered an army in 490 and sent it to Greece. This time he has two commanders: the Lydian Artaphernes leads the Persians on the sea, and the Mede Datis leads the Persians on land.

Soldiers sweep through Naxos like a hurricane, punishing the inhabitants for the recently raised uprising, besiege Eritrea and after 6 long months enter the city, set it on fire and plunder it, avenging the devastated Sardis. And they rush to Attica, crossing the Euripus Strait.

Greco-Persian Wars. 490 BC e. Marathon Battle

Photo: godsbay.ru

Photo: godsbay.ru 490 BC: Athens is in great danger. The Persians, having dealt with the uprisings in their own territories, began to attack their allies. A large army gathered on the Marathon plain, threatening the freedom of the Hellenes.

The location was not chosen by chance: the Persian cavalry, as the main striking force, could operate as efficiently as possible in such conditions. The Athenians, having asked for help from their allies (of which, however, only the inhabitants of Plataea decided to help; the Spartans, citing a divine holiday, did not appear on the battlefield), also settled down near Marathon.

Of course, it was possible to hide behind the city walls, but the fortifications of Athens were not very reliable. And the Hellenes were afraid of betrayal, like what happened in Eritrea, where the eminent citizens Philagrus and Euphorbus opened the gates of the city to the Persians.

The Athenians took a rather advantageous position: the height of Pentelikon, blocking the passage to the city. The question arose about further strategy. The opinion of the members of the military council, headed by Callimachus, was divided. But the most gifted and talented strategist, Miltiades, managed to convince everyone to go on the offensive. The tactics for further actions were developed by him.

Photo: wallpaper.feodosia.net

Photo: wallpaper.feodosia.net The Persians decided to avoid battle and moved towards the ships, intending to leave the Marathon field and land near Athens in the town of Falera. But after half of the armed Persian soldiers had already boarded the ships, the combined forces of the Greeks dealt a crushing blow: during the battle that took place in 490 BC. e., on September 12, about 6,400 Persians and only 192 Hellenes were killed.

The Persians set out to attack Athens, which seemed unprotected. But Maltiades sent a messenger, who, according to legend, ran 42 kilometers and 195 meters without stopping to report a grandiose victory and warn the city residents about a possible attack. This distance is currently included in the program Olympic Games, that’s what they call a marathon.

The commander himself and his army also quickly reached the city. The Persians, making sure that Athens was well protected, were forced to return to their homeland. Darius's punitive campaign failed. And a further attack on the Greeks remained just plans: a much more dangerous rebellion was brewing in Egypt.

Greco-Persian Wars. 480-479 BC e. Campaign of Xerxes

Photo: pozdravimov.ru

Photo: pozdravimov.ru Darius I died without taking revenge on the Greek offenders. But his successor Xerxes was not satisfied with this state of affairs. The suppression of the Egyptian uprising did not exhaust the enormous resources of Persia, which was at the peak of its power: it was decided to continue what Darius had started and capture rebellious Greece. Xerxes began to gather armies of conquered peoples under his banners.

But the Greeks also did not sit idle. On the initiative of the far-sighted politician Themistocles, the Athenians create a powerful fleet, and also hold a congress, where representatives of 30 Greek city-states are present. At this event, the Hellenes agree to act together against a common enemy. The army assembled by the Greeks is indeed very powerful: the well-armed Athenian fleet, which also includes ships sent by Aegina and Corinth, under the command of Eurybiades, a native of Sparta, is a formidable force at sea, and its warlike brethren, with the support of its allies, must resist the enemy's ground forces.

The Greeks had to prevent the advance of Xerxes' troops deep into Hellas at any cost. This could only be done by placing soldiers in the narrow gorge of Thermopylae and barricading the strait with ships near Artemisium, the cape next to which the path to Athens lay.

Photo: worldunique.ru

Photo: worldunique.ru Two battles: the Battle of Thermopylae and the Battle of Artemisium ended unsuccessfully for the Greeks. The most famous event of the first is the death of 300 Spartans led by King Leonidas, who heroically defended the narrow passage. The Greeks might have survived in the gorge if not for the betrayal of the inhabitants, so characteristic of those times. Following the defeat on land was the retreat of the fleet. The Persians fought their way to Athens.

Thanks to the cunning of Themistocles, the Athenian orator, and the shortsightedness of the Persian king, the next battle between the opponents took place in the narrow straits near the island of Salamis. Here luck was on the side of the Greeks.

However, in 479 the Persians managed to occupy Athens (the inhabitants were evacuated to Salamis). However, not for long: in the Battle of Palatei they again lost their advantage, this time completely. The Greco-Persian wars were effectively over.

However, everything is not as simple as it seems at first glance. The Hellenes, having gained an advantage, began to advance into Persian territory. The Greeks were able to conquer vast territories and even reach the most troubled province that was part of the enemy empire - Egypt. The conflict will finally end only in 449 BC. e., 50 years after the events began. But this is a completely different story, and we will tell it next time...

That's all we have . We are very glad that you visited our website and spent a little time to gain new knowledge.

Join our

People have been fighting since time immemorial. Some peoples tried to conquer other, weaker ones. This uncontrollable thirst for blood, profit, and power over others led to the emergence of entire eras that can only be told about wars. Every person knows that the real cradles of Western and Eastern civilization are Hellenic Greece and Persia, but not everyone knows the fact that both of these cultural titans fought among themselves at the turn of the 5th - 6th centuries BC. In addition to devastation and losses, the Greco-Persian War brought heroes to the world.

The conflict was truly a turning point in the entire history of the ancient world. Many facts are unclear to this day, but the tireless work of scientists will certainly bear fruit. On at this stage we can only slightly lift the veil of secrecy over this truly terrifying, but at the same time mind-shattering historical event. All sources known to date were inherited from scientists and travelers who lived at that time. The authenticity of the Greco-Persian War is unconditional, but the scale is simply impossible to imagine, since the two most powerful powers of that time fought.

Brief description of the period

The Greco-Persian Wars is a collective concept of one period during which military conflict occurred between the independent city-states of Greece and Persia, under the Achaemenid dynasty. We are not talking about a single military skirmish of a prolonged nature, but about a whole series of wars that were fought from 500 to 449 BC. Actions of this magnitude were caused primarily by the conflict of interests between Greece and the Persian state.

The Greco-Persian Wars include all armed campaigns of the Persians against the states of the Balkan Peninsula. As a result of the war, Persia's large-scale expansion to the west was stopped. Many modern scientists call this period fateful. It is difficult to imagine the further development of events if the East nevertheless conquered the West.

It is impossible to describe the Greco-Persian wars briefly. This historical period requires detailed study. To do this, you need to turn to the sources of that time.

main sources

The history of the Greco-Persian wars is rich in events and personalities. The information that has reached us allows us to accurately recreate the picture of the events of those years. Almost everything that modern historians know about the Greco-Persian War comes from ancient Greek treatises. Without the knowledge that was taken from the works of scientists of Ancient Greece, people would not have been able to obtain even a small fraction of the knowledge available to them today.

The most important source is a book called History, written by Herodotus of Halicarnassus. Its author traveled half the world, collecting various data about the peoples and other historical events of the era in which he lived. Herodotus tells the story of the Greco-Persian War, from the conquest of Ionia to the defeat of Sestus in 479 BC. The description of all events makes it possible to literally see all the battles of the Greco-Persian wars. However, this source has one significant drawback: the author was not a witness to all those events. He was simply retelling what other people had told him about. As we understand, with this approach it is very difficult to distinguish lies from truth.

After the death of Herodotus, Thucykides of Athens continued the work. He began to describe events from the point where his predecessor left off, and ended with the end of the Peloponnesian War. The historical brainchild of Thucydides is called: “The History of the Peloponnesian War.” In addition to the presented scientists, other historians of antiquity can be distinguished: these are Diodorus Siculus and Ctesias. Thanks to the memoirs and works of these people, we can analyze the main events of the Greco-Persian wars.

What contributed to the start of the war

Today we can identify a large number of factors that literally brought the Greco-Persian wars to the land of Ancient Hellas. The reasons for these events are perfectly described in the works of Herodotus, who is also called the “father of history.” According to the data he provided, during the Dark Ages colonies were formed on the shores of Asia Minor. These small cities were mainly inhabited by tribes of Aeolians, Ionians and Dorians. A number of established colonies had complete independence. In addition, a special cultural alliance was concluded between them. Similar cooperation closed type right on the shores of Asia Minor, it did not exist independently for long. The alliance turned out to be so shaky that within a few years King Croesus conquered all the cities.

Conflict between Persians and Greeks

The reign of the self-proclaimed king did not last long. Soon the founder of the Achaemenid dynasty, Cyrus II, conquered the resulting state.

From this time on, the cities came under complete control of the Persians. But a series of military conflicts begins a little later, at least that’s what Herodotus tells. The Greco-Persian wars, in his opinion, begin in 513 BC, when Darius I organizes his campaign in Europe. Destroying Greek Thrace, his troops encountered an army of Scythians, which they could not defeat.

The most intense political conflict erupted between the Persians and Athens. This center of ancient Greek culture endured the attacks of the tyrant Hippias for a very long time. When he was finally driven out, a new threat arrived - the Persians. Once under their rule, many Athenians showed discontent, reinforced by the order of the Persian commander, according to which Hippias returned back to Athens. It was from this moment that the Greco-Persian wars began.

March of Mardonius

The chronology of the Greco-Persian wars begins from the moment when Mardonius, son-in-law of Darius, moved straight to Greece, through Macedonia and Thrace. However, the dreams of this ambitious military leader were not destined to come true. The fleet, consisting of more than 300 ships, was completely smashed against the rocks by a storm, and the land forces were attacked by barbarian brigs. Of all the planned territories, only Macedonia was conquered.

Artapherna Company

After the terrible failure of Mardonius, the general Artaphernes took command, with the support of his close friend Datis. The main purpose of the campaign was as follows:

1. Subjugation of Athens.

2. The defeat of Eretria on the island of Euboea.

Darius also ordered the inhabitants of these cities to be brought to him as slaves, which would symbolize the complete conquest of Greece. The primary goals of the campaign were achieved. In addition to Eretria, Naxos was conquered. But the losses of the Persian army were colossal, because the Greeks resisted with all their might, thereby exhausting the enemy.

Marathon Battle

The Greco-Persian Wars, the main battles of which took place quite epically, wrote the names of some commanders into history. For example, Miltiades - this talented commander and strategist was able to brilliantly use the small number of advantages that the Athenians had during the Battle of Marathon. Miltiades was the initiator of the battle between the Persians and Greeks. Under his command, the Greek army launched a massive attack on enemy positions. Most of the Persian army was thrown into the sea, the rest was killed.

In order not to completely lose the campaign, Artaphernes' army begins to advance by ship along Attica with the goal of conquering Athens while the city does not have enough forces to defend it. At the same time, the Greek army immediately after a long battle took a march towards the capital of all Greece. These actions have borne fruit. Miltiades and his entire army managed to return to the city before the Persians. Artaphernes' exhausted army retreated from Greek soil because further battle was pointless. Prominent Athenian politicians prophesied that the Greeks would lose all the Greco-Persian wars. The Battle of Marathon completely changed their minds. Darius's campaign ended in complete failure.

Break from the war and construction of the fleet

The Athenians understood that the results of the Greco-Persian wars would depend on many factors. One of these was the presence of a fleet. The fact that the Persians would continue the war was not even questioned. The famous politician and skillful strategist Themistocles proposed strengthening his fleet by increasing its number. The idea was received ambiguously, especially by Aristide and his followers. Nevertheless, the threat of the Persians had a much greater effect on the consciousness of people than the danger of losing a small amount Money. Aristides was expelled and the fleet increased from 50 to 200 ships. From this moment on, the Greeks could count not only on survival, but also on victory in the war with Persia.

Beginning of Xerxes' campaign

After the death of Darius I (in 486 BC), his son, the cruel and reckless Xerxes, ascends to the Persian throne. He was able to gather a huge army, the likes of which had never before been seen in Asia Minor. In his historical writings, Herodotus tells us about the size of this army: about 5 million soldiers. Modern scholars are skeptical about these figures, insisting that the number of the Xerxes army did not exceed 300,000 soldiers. But the greatest danger came not from the soldiers themselves, but from the fleet of 1,200 ships. Such naval power really brought real horror to the Athenians, who had nothing at all: 300 ships.

Battle of Thermopylae

The offensive of Xerxes' army began in the area of the Thermopylae Pass, which separated northern Greece from central Greece. It was in this place that the famous story of three hundred Spartans led by King Leonidas began. These warriors bravely defended the passage, inflicting heavy losses on the Persian army. The geography of the area was on the side of the Greeks. The size of Xerxes' army did not matter because the passage was quite small. But in the end, the Persians made their way, having previously killed all the Spartans. However, the strength of the Persian army was irrevocably undermined.

Naval battles

The defeat of Leonidas forced the Athenians to leave their city. All residents crossed to the Peloponnese and Enigma. The forces of the Persian army were running out, so it did not pose much of a threat. Plus, the Spartans were well entrenched on the Isthmus Isthmus, which significantly blocked the path of Xerxes. But the Persian fleet still threatened the Greek army.

The previously mentioned strategist Themistocles put an end to this threat. He literally forced Xerxes to take battle at sea with his entire unwieldy fleet. This decision became fatal. The Battle of Salamis marked the end of Persian expansion.

All further actions by the Greek army were aimed at the complete destruction of the Persians. The Greeks slowly drove the enemy out of the expanses of Thrace, took away half of Cyprus, as well as cities such as Chersonesos, Rhodes, and the Hellespont.

The Greco-Persian Wars ended with the signing of the Peace of Potassium in 449 BC.

Results

Thanks to the tactics, fortitude and courage of the Greeks, the Persians lost all their possessions in the Aegean Sea, as well as on the coasts of the Bosphorus and Hellespont. After the events of the war, the spirit and self-awareness of the Greeks increased noticeably. The fact that Athenian democracy contributed greatly to the victories sparked massive democratic movements throughout Greece. From that moment on, the culture of the East began to gradually fade against the background of the great West.

Greco-Persian Wars: Event Table

Conclusion

So, the article examined the Greco-Persian wars. Summary of all events allows you to get acquainted in detail with this difficult period in the history of ancient Greece. This turning point shows the power and indestructibility of Western culture. A new era began when the Greco-Persian wars ended. The reasons, main events, persons and other facts still cause a lot of controversy among modern scientists. Who knows what other incredible information the period conceals? great war between West and East.

In the middle of the 1st millennium BC. e. Hellas (Greece) begins to play an increasingly prominent role in the history of the Eastern Mediterranean. By this time, the Greeks, despite the preservation of tribal divisions and peculiarities in language and way of life, represented an established nationality. The far-reaching process of property stratification, the growth of private property and the formation of classes undermined the old, clan organization. Its place is taken by the state, the specific form of which for ancient Greece was the polis - the ancient city-state.

The polis was a civil community, membership of which gave its individual members the right of ownership to the main means of production of that time - land. However, not the entire population living on the territory of a particular policy was part of the community and enjoyed civil rights. Slaves were deprived of all rights; in addition, in each policy there were various categories of personally free, but not full-fledged population, for example, immigrants from other policies, foreigners. Slaves and inferiors were usually most population of the policy, and citizens are a privileged minority. But this is a minority, having completeness political power, used it to exploit and oppress slaves and other categories of dependent or disadvantaged population. In some policies, only the upper strata of citizens enjoyed political predominance (aristocratic polis), in others - a wider circle of citizens (democratic polis). But both policies were slaveholding.

Greece on the eve of the Greco-Persian Wars

In ancient times, Hellas was a sum of independent and self-governing city-states, which, due to the historical situation, either entered into an alliance with each other, or, on the contrary, were at enmity with each other. A number of large Greek city-states arose on the coast of Asia Minor (Miletus, Ephesus, Halicarnassus, etc.). They early turned into rich trade and craft centers. In the second half of the 6th century. BC e. all the Greek cities of the Asia Minor coast fell under Persian rule.

Large Greek city-states also arose on the islands of the archipelago and on the territory of Balkan Greece itself. During the period of greatest development of Greek colonization (VIII-VI centuries BC), the framework of the Hellenic world expanded widely. The successful advance of the Greeks in the northeastern direction leads to the emergence of a number of policies on the southern (Sinoda, Trebizond), and then on the northern (Olbia, Chersonesus, Panticapaeum, Feodosia) and eastern (Dioscurias, Fasis) coast of the Black Sea. Greek colonization is developing even more intensively in a western direction. The number of Greek colonies in southern Italy and Sicily was so large that this area was still in the 6th century. received the name "Magna Graecia".

The entire coast of the Gulf of Tarentum is surrounded by a ring of rich and flourishing cities (Tarentum, Sybaris, Croton, etc.), then the Greeks penetrate deep into southern Italy (Naples) and into the eastern part of Sicily (Syracuse, Messana, etc.). The city-states of Magna Graecia became an increasingly prominent political force in the complex international struggle that unfolded in the 6th-5th centuries. BC e. in the Western Mediterranean basin.

However, the center of development of this vast and widely spread Greek world by the beginning of the 5th century. BC e. is the Balkan Peninsula, the territory of Greece proper. Here, by this time, the two most significant city-states stood out - Sparta and Athens. The development paths of these states were different. The Spartan community was agrarian, agricultural in nature; trade and monetary relations were poorly developed here. The land, divided into approximately equal plots (kleri) and used by individual Spartiate families, was considered the property of the community, the state as a whole, and an individual Spartiate could own it only as a member of the community. These lands were cultivated by the labor of a population without rights, dependent and attached to the clergy - the helots. Unlike the usual type of slavery in Greece, helots did not belong to individual Spartiates, but were considered the property of the community as a whole. In Sparta, there was also a special category of disadvantaged population - perieki (“living around”, i.e. not on the territory of the city of Sparta itself). Their situation was less difficult. They owned property and land on a private basis and were engaged not only in agriculture, but also in crafts and trade. Wealthy Perieci owned slaves.

Athens was a different type of slave city-state. The intensive growth of the productive forces of Athenian society, associated with the development of crafts and maritime trade, led to the relatively early decomposition of the community. In Athens, as a result of the struggle that unfolded between broad sections of the population (demos) and the tribal aristocracy (eupatrides), a slave state emerged, which received a rather complex social structure.

The free population of Athens was divided into a class of large slave-owning landowners and a class of free producers. The first of them should include, in addition to the eupatrids, representatives of the new trading and monetary nobility, the second - broad layers of the demos, i.e. peasants and artisans. There was another division of the free part of the Athenian population: into those who enjoyed political rights and those without full rights - into citizens and meteks (foreigners living in the territory of Athens). Slaves, completely deprived of civil rights and personal freedom, stood lowest on the social ladder.

The government systems of Athens and Sparta also had significant differences. Sparta was a typical oligarchic republic. The community was headed by two kings, but their power was severely limited by the council of elders (gerusia) - the body of the Spartan nobility - and the college of ephors, who played a major role in political life. Although the People's Assembly (apella) was formally considered the supreme body of power, in fact of great importance didn't have.

In Athens, as a result of transformations carried out in the 6th century. Solon and Cleisthenes established a system of slave-holding democracy. The political dominance of the clan nobility was broken. Instead of the previous tribal phyla, territorial phyla appeared, subdivided into padems. The role of the Athenian people's assembly (zkklesia) grew more and more. The main government positions were elected. The elected “council of five hundred” (bule) gradually pushed into the background the stronghold of the tribal nobility - the Areopagus, although the latter at the beginning of the 5th century. still represented a certain political force. A democratic body was created as a jury (heliea), the composition of which was replenished by drawing lots from among all full-fledged citizens. Economic and political system Greek states were also determined by their character military organization. In Sparta, a unique way of life and a system of militarized education, based on the institutions attributed to the legendary legislator Lycurgus, contributed to the creation of a strong and experienced army (Spartan infantry). Sparta subjugated Kynuria and Messenia and headed the Peloponnesian League, which included the Arcadian cities, Elis, and then Corinth, Megara and the island of Aegina. Athens, as a trading and maritime state, developed mainly shipbuilding. By the beginning of the 5th century. The Athenian fleet, especially the military one, was still small. However, everything economic development The Athenian state, and then the military threat hanging over it, pushed the Athenians onto the path of intensive fleet construction. Since service in the navy was mainly the lot of the poorest citizens, the growth of the Athenian fleet was closely connected with the further democratization of the political system, and the lower command staff and rowers of the fleet were the support of slave-owning democracy. Soon the question of the importance of the fleet for the Athenian state arose in full force. This happened in connection with the Persian attack on Greece.

The beginning of the Greco-Persian wars. Campaigns of Darius I in Balkan Greece

After the suppression of the uprising of the Greek cities of Asia Minor, the Persian ruling circles decided to use the fact that the Athenians provided assistance to the rebels as a pretext for war against the European Greeks. The Persians, as already mentioned, understood that they could strengthen their possessions in Asia Minor only after conquering mainland Greece. Therefore, in the summer of 492, under the command of Darius's son-in-law, Mardonius, the first land-sea campaign was undertaken along the Thracian coast to Balkan Greece. As Mardonius' forces approached the Chalkidiki peninsula, his fleet was caught in a storm off Cape Athos, during which up to 300 ships and their crews were lost. After this, Mardonius, leaving garrisons on the Thracian coast, was forced to turn back. In 490 BC. e. The Persians launched a second campaign against Greece. Persian troops crossed the Aegean Sea by ship, devastated the island of Naxos and the city of Eretria on Euboea along the way, and then landed on the Attica coast near Marathon. The danger of a Persian invasion loomed over Athens. Their appeal to Sparta for help did not produce the expected result: Sparta chose to take a wait-and-see approach. The Athenians themselves could field only 10 thousand heavily armed soldiers; about a thousand soldiers sent to their aid Plata, a small Boeotian city located near the border with Attica. We do not have reliable data on the number of Persians who landed at Marathon, but one can think that there were at least no fewer of them than the Greeks. At the council of Athenian strategists, it was decided to meet the enemy and give him battle at Marathon. This decision was determined not only by military, but also by political considerations. There were many aristocrats in the city, as well as supporters of the political regime that existed in Athens under the tyrant Pisistratus and his sons. When enemies approached the city, they could go over to the side of the Persians. Command over the army that marched to Marathon was entrusted to strategists, including Miltiades, the ruler of Thracian Chersonesus who fled from the Persians, to whom the military techniques of the Persians were well familiar.

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC. e. and culminated in the complete victory of the Athenians and their Plataean allies. The Persians could not withstand the attack of the closed formation of heavily armed Greek soldiers, were overthrown and put to flight. Herodotus says that they left up to 6,400 corpses on the battlefield, while the Greeks lost only 192 people killed. This victory, won by the citizens of the Greek polis, inspired by patriotic feelings, over the troops of the strongest power of that time, made a huge impression on all Greeks. Those of the Greek cities that had previously submitted to Darius again declared themselves independent. Almost simultaneously, unrest arose in Babylonia, and uprisings even broke out in Egypt and distant Nubia.

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC. e. and culminated in the complete victory of the Athenians and their Plataean allies. The Persians could not withstand the attack of the closed formation of heavily armed Greek soldiers, were overthrown and put to flight. Herodotus says that they left up to 6,400 corpses on the battlefield, while the Greeks lost only 192 people killed. This victory, won by the citizens of the Greek polis, inspired by patriotic feelings, over the troops of the strongest power of that time, made a huge impression on all Greeks. Those of the Greek cities that had previously submitted to Darius again declared themselves independent. Almost simultaneously, unrest arose in Babylonia, and uprisings even broke out in Egypt and distant Nubia.

But the Persians did not think of abandoning their plan to conquer Greece. However, in 486 Darius died, and court unrest began due to the transfer of power to new hands. Therefore, only 10 years after the Battle of Marathon, Darius’s successor, King Xerxes, was able to launch a new big campaign against the Greeks.

The Greeks made poor use of the ten-year break to prepare for the resumption of war. The only exception in this regard was Athens. Here at this time there was an intense political struggle between the aristocratic and democratic groups. The democratic group was led by Themistocles, one of the most courageous, energetic and far-sighted figures of this time. According to the Greek historian Thucydides, Themistocles, like no one else, had the ability to foresee “the best or worst outcome of an enterprise, hidden in the darkness of the future,” and was able in all cases to “instantly invent an appropriate plan of action.” Themistocles’ group, along with merchants and wealthy artisans, also included broader sections of the civilian population of Athens, who shared the so-called naval program he put forward - a broad plan for strengthening the naval power of Athens and building a new fleet. Their opponents, led by Aristide, found support among large landowners. In the end, the naval program was adopted by the people's assembly. Carrying out this program, the Athenians built about 150 warships (gprier) using income from the Daurian mines, previously distributed among citizens. After this, the Athenian fleet became the strongest in Greece.

Campaign of Xerxes

Military operations resumed in the spring of 480. A huge fleet and land army, consisting of both the Persians themselves and detachments fielded by the conquered peoples who were part of the Achaemenid power, moved, led by Xerxes himself, through the Hellespont along the Thracian coast along the route of Mardonius’s first campaign to Balkan Greece. The Greek city-states, who decided to resist, entered into a defensive alliance, headed by Sparta, as the state that had the strongest ground forces. On the border between Northern and Central Greece, small Allied forces occupied the narrow Thermopylae pass, which was convenient for defense. Xerxes' troops attacked the defenders of Thermopylae many times, trying in vain to break through the defenses. But among the Greeks, there was a traitor who showed the enemies a bypass mountain path)". Along this path, a detachment of Persians went to the rear of the defenders of Thermopylae. When the Spartan king Leonidas, who commanded the allied forces, became aware of this, he ordered his troops to retreat, but he himself A detachment of Spartan warriors of 300 people remained in Thermopylae. Surrounded on all sides by enemies, the Spartans fought to the last man. Subsequently, a monument was erected on the grave of Leonidas and his soldiers with the inscription:

Military operations resumed in the spring of 480. A huge fleet and land army, consisting of both the Persians themselves and detachments fielded by the conquered peoples who were part of the Achaemenid power, moved, led by Xerxes himself, through the Hellespont along the Thracian coast along the route of Mardonius’s first campaign to Balkan Greece. The Greek city-states, who decided to resist, entered into a defensive alliance, headed by Sparta, as the state that had the strongest ground forces. On the border between Northern and Central Greece, small Allied forces occupied the narrow Thermopylae pass, which was convenient for defense. Xerxes' troops attacked the defenders of Thermopylae many times, trying in vain to break through the defenses. But among the Greeks, there was a traitor who showed the enemies a bypass mountain path)". Along this path, a detachment of Persians went to the rear of the defenders of Thermopylae. When the Spartan king Leonidas, who commanded the allied forces, became aware of this, he ordered his troops to retreat, but he himself A detachment of Spartan warriors of 300 people remained in Thermopylae. Surrounded on all sides by enemies, the Spartans fought to the last man. Subsequently, a monument was erected on the grave of Leonidas and his soldiers with the inscription:

Traveler, go and tell our citizens in Lacedaemono that, keeping their covenants, here we died in bones.

Having broken through Thermopylae, the Persians poured into Central Greece. Almost all the Boeotian cities, in which the Persophile-minded aristocracy was strong, hastened to submit to Xerxes. Attica was devastated, Athens was plundered. The Athenians evacuated children, women and the elderly to the Peloponnese and nearby islands; however, men capable of carrying weapons moved to the decks of warships. The Greek ground forces strengthened on the Isthmus of Corinth. The fleet that fought at Cape Artemisia (in the north of Euboea), in which more than half of the ships belonged to the Athenians, retreated to the Saronic Gulf.

The turning point in the war was the famous naval battle off the island of Salamis (480 BC). Having divided their fleet, the Persians attacked the enemy from two sides at once. The Greek ships moved towards them. In the narrow strait between the shores of Attica and Salamis, the Persians were unable to use their numerical superiority. With a rapid onslaught, the Greeks upset the battle formation of their ships, which were larger in size than the Greek ones and less capable of maneuvering; in the cramped conditions, the Persian ships collided and sank each other. By nightfall the Persian fleet was defeated.

The victory at Salamis was primarily the merit of the Athenians, led by the strategist Themistocles. The defeat that the Persians suffered here was a heavy blow for them. Although they still had a large and fully combat-ready ground army, its connection with the rear could easily be interrupted. In addition, the news of a major defeat of the Persian fleet threatened to cause unrest within the Persian state itself, primarily in Ionia. Therefore, Xerxes decided to return to Asia, leaving in Greece part of the army under the command of Mardonius. The following year, 479, Mardonius, having spent the winter with his troops in Thessaly, returned to Central Greece and approached the Isthmian Isthmus. The combined forces of the Greek allies under the command of the Spartan Pausanias settled near Plataea. In the battle that took place here soon, the troops of Mardonius were completely defeated and he himself was killed. In the same 479, the Greek fleet, led by the Athenian strategist Xanthippus and the Spartan king Leotychides, won a brilliant victory over the Persians in the battle of Cape Mycale (the coast of Asia Minor).

The victory at Salamis was primarily the merit of the Athenians, led by the strategist Themistocles. The defeat that the Persians suffered here was a heavy blow for them. Although they still had a large and fully combat-ready ground army, its connection with the rear could easily be interrupted. In addition, the news of a major defeat of the Persian fleet threatened to cause unrest within the Persian state itself, primarily in Ionia. Therefore, Xerxes decided to return to Asia, leaving in Greece part of the army under the command of Mardonius. The following year, 479, Mardonius, having spent the winter with his troops in Thessaly, returned to Central Greece and approached the Isthmian Isthmus. The combined forces of the Greek allies under the command of the Spartan Pausanias settled near Plataea. In the battle that took place here soon, the troops of Mardonius were completely defeated and he himself was killed. In the same 479, the Greek fleet, led by the Athenian strategist Xanthippus and the Spartan king Leotychides, won a brilliant victory over the Persians in the battle of Cape Mycale (the coast of Asia Minor).

The end of the war and its historical significance

After Salamis and Plataea, the war was not over yet, but its nature had changed radically. The threat of enemy invasion ceased to weigh heavily on Balkan Greece, and the initiative passed to the Greeks. In the cities of the western coast of Asia Minor, uprisings against the Persians began; the population overthrew the rulers installed by the Persians, and soon all of Ionia regained its independence.

In 467, the Greeks dealt another blow to the military forces of the Persian state in a battle at the mouth of the Eurymedon River (on the southern coast of Asia Minor). Military operations, either calming down or resuming again, continued until 449, when in the battle near the city of Salamis on the island of Cyprus the Greeks won a new brilliant victory over the Persians. This battle of Salamis is considered the last battle in the Greco-Persian wars; in the same year, as some Greek authors report, the so-called Callian peace (named after the Athenian commissioner) was concluded between both sides, under the terms of which the Persians recognized the independence of the Greek cities of Asia Minor.

The main reason for the victory of the Greeks over the Persians in this historical clash was that they fought for their freedom and independence, while the troops of the Persian state consisted largely of forced soldiers who were not interested in the outcome of the war. It was also extremely important that the economic and social life of Greece at that time reached a relatively high level of development, while the Persian power, which forcibly included many tribes and nationalities, hampered the normal development of their productive forces.

The victory of the Greeks in the clash with the Persians not only ensured the freedom and independence of Greek cities, but also opened up broad prospects for further unhindered development. This victory was thus one of the prerequisites for the subsequent flourishing of the Greek economy and culture.

The Greco-Persian Wars are the most significant wars in the history of Ancient Greece. They are described in most detail in the work “History”, which was written by Herodotus, who lived in the 5th century BC. e. He traveled a lot, visited Persia and other countries. By the time of the wars with the Greeks, the Persian Empire included many countries and peoples. Therefore, Herodotus decided to first tell about the history of Persia and the lands it conquered. He was later called the "father of history" because he was the first to write a real historical work.

1. Causes of the Persian-Greek war.

The Persian kingdom, headed by King Darius I, was then the most powerful state in the world. The Greek cities of Asia Minor were also under his rule. The Persians subjected them to tyrants and forced them to pay heavy taxes.

The Greeks hardly tolerated this oppression. In 500 BC. e. An uprising broke out in Miletus, which spread to other cities. The rebels turned to free policies for help. But only Athens and Eretria (a city on the island of Euboea) sent 25 ships. At first the Greeks won several victories, but then were defeated.

2. Persian campaign. Darius swore revenge on the Athenians and Euboeans, but his plans were more ambitious - he sought to conquer all of Greece. Darius sent envoys to the policies demanding “land and water,” that is, complete submission.

Many expressed their resignation. Only Athens and Sparta resolutely refused. The Spartans threw the royal envoys into the well, saying: “If you want, you can take the land and water there yourself!”

In 490 BC. e. The Persian fleet approached Attica from the north, and the army landed at the small village of Marathon. The Athenians immediately sent their militia there. From all of Hellas, only citizens of the small town of Plataea in Boeotia came to their aid. The Persians significantly outnumbered the Greeks in number of warriors.

3. Battle of Marathon. The Athenian commander Miltiades formed a phalanx of soldiers in such a way that the Greeks were able to break the resistance of the Persians. The Hellenes pursued them all the way to the sea. Here they attacked the ships, which began to quickly move away from the shore, abandoning their warriors. The Greeks won a brilliant victory.

As the legends say, having received the order, one of the young warriors ran to Athens. The citizens of the city were languishing in uncertainty, and it was necessary to tell them the good news of the victory as quickly as possible. Without stopping once, without drinking a sip of water, the warrior ran 42 km 195 m. This was the distance between the battlefield and Athens. Appearing in the square, he stopped and shouted: “Rejoice, Athenians, we have won!” - and immediately fell lifeless. Nowadays, there is a running competition over a distance of 42 km 195 m, which is called marathon running.

The victory at Marathon changed the mood of all the Greeks. She destroyed the legend of Persian invincibility. The Athenians themselves were prouder of their victory at the Battle of Marathon than any other in their history.

4. The Greeks are building a fleet. The war did not end after the Battle of Marathon. The Greeks just got a break. During these years, the talented and energetic politician Themistocles began to enjoy great influence in Athens. He saw the salvation of Greece in the fleet. Just at this time, a rich silver deposit was discovered in Attica. Themistocles proposed to spend the proceeds from its development on the construction of warships. 200 triremes were built.

5. The campaign of the Persian king Xerxes. Only 10 years later the Persians were able to begin a new campaign against Greece. It was headed by King Xerxes, who replaced Darius. The army of Xerxes moved towards Hellas from the north by land, and a huge fleet accompanied it along the seashore. Many policies united against the formidable enemy, handing over the supreme command to Sparta.

6. Battle of Thermopylae (480 BC). They decided to fight in the gorge between Northern and Central Greece at Thermopylae. The mountains in this place come close to the sea, and the passage is very narrow. It was defended by several thousand Greeks, including a detachment of 300 Spartans. The Spartan king Leonidas commanded the entire army. There were many times more Persians. Xerxes sent a messenger to Thermopylae with two words: “Lay down your arms.” Leonid also answered with two words: “Come and take it.”

The bloody battle lasted two days. The Persians could not break through. But there was a traitor who led them along the mountain paths. The enemies found themselves behind Greek lines. When Leonidas found out about this, he ordered everyone to leave, while he remained with the Spartans and volunteers. The Hellenes fought with insane courage. They all died in a fierce battle. But many enemies were also killed.

Later, in the Thermopylae Gorge they erected a statue of a lion (Leonidas in Greek means “lion cub”) and a stone with the inscription: “Traveler, inform Lacedaemon that we lie here, having honestly fulfilled the law.”

7. Battle of Salamis (480 BC). The Persian army marched towards Athens. Residents left the city. Women, children and old people were sent to neighboring islands, all men were on ships. Now all hope was in the fleet. It consisted of approximately 400 ships, half of them from Athens. The battle took place in the Strait of Salamis between the island of Salamis and the coast of Attica. At dawn, Persian ships entered the strait. The Athenian ships quickly attacked the advanced enemy ships. Light triremes easily bypassed heavy enemy ships. The Persians fought for booty and rewards from the king, the Greeks - for freedom and life. The Athenians saw columns of black smoke rising above the houses and temples of their city that were set on fire by the Persians. Their parents, wives, sisters, and children were nearby on the islands. The Greeks had to either die or become slaves. This increased their strength; no one thought about the danger.

Most of the enemy ships were killed, the rest retreated. Despite the enemy's numerical superiority, the Greeks won. Xerxes with the surviving ships retreated to Asia Minor, but left part of the army in Greece.

8. Battles of Plataea and Mycale (479 BC). Now one could think about expelling all Persians from Greece. In 479 BC. e. A battle took place near the town of Plataea in Boeotia. The battle was long and bloody. But the Greek hoplites were better trained, had more advanced weapons, and fought for freedom. And they won. According to legend, on the same day the Greeks won a second victory - at Cape Mycale near Miletus. They attacked the enemy simultaneously from sea and land, destroyed a strong Persian army and burned most of the enemy ships.

The gradual liberation of the Greek cities located here began.

9. Results of the Greco-Persian Wars. The war continued for a long time. The leadership of the allied forces of the Greeks now passed into the hands of Athens. Finally, in 449 BC. e. peace was concluded. The Persian king recognized the independence of all Greek cities of Asia Minor. The Persian fleet had no right to appear in the Aegean Sea. Athens emerged from the war as the strongest maritime state in Greece.

Why did the Greeks win the war? After all, their forces were numerically much inferior to the army of the huge Persian Empire. The most important reason for the victory was that the Greeks were defending their homeland and independence. And the Persian army largely consisted of forced soldiers. Sometimes it was even necessary to drive them into battle with whips. The military superiority of the Greeks also played a major role. Their warriors were better armed and trained.