Development of a lesson on literature “Two types of folk singers” (based on the story “Singers” by I.S. Turgenev)

Speech development lesson. 7th grade

Detailed presentation.

Jacob's singing.

Goals:

- Remember the features of styles and types of speech, the composition of texts describing actions.

- Teach text analysis, detailed presentation, maintaining structure and style.

- Learn to express your thoughts competently, beautifully, consistently, and practice the ability to use known means of language when retelling.

Lesson material

- Nikitina E.N. “Russian speech” §39, table p.178-179, memo p.180

- Text “Singing of Jacob” - 15 pcs.

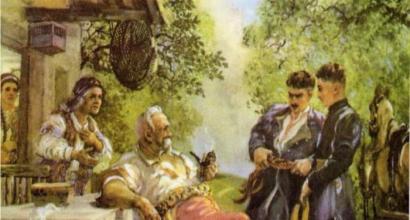

- Illustration from I. S. Turgenev’s book “Notes of a Hunter” by artist An. Belyukin

- Explanatory dictionary of the Russian language

Board design

1 board. Interpretation of words

2 board. Date of. Subject. Plan

3 board. Vocabulary work

During the classes

- Organizing time

- Lesson objective: Guys, today we are writing a summary of the text “Jacob’s Singing” (an excerpt from I.S. Turgenev’s story “The Singers.” The text is in front of you. Your task is to concentrate, remember everything that we taught you and use these skills in practice. The work is not new for us.

Speech task.

Today we are writing a detailed presentation, which means we need to try to preserve the style of this text, convey the content in as much detail as possible using the means of language used by the author, without breaking the sequence or distorting the main idea.

- Preparation for perception.

Let's return to the passage. It is taken from the story "The Singers". You read this story in the summer. Who is the author and what book is it taken from? (I.S. Turgenev “Notes of a Hunter”). This book contains 25 essays, each with its own plot, and at the same time included in a single narrative cycle, secured by the position of the narrator, acting as a character, a hunter.

Often the heroes of the stories, as in the story “The Singers,” were serfs. This is due to the fact that the writer swore an oath to himself never to reconcile himself with serfdom.

No one ever considered the “peasant” a person; in the eyes of the highest noble society, he was a creature of the lowest grade, a dumb slave, incapable of high feelings.

Turgenev proves with his book that the “man” is not just a person, but a wonderful person, possessing both understanding and high feelings, which people educated from privileged classes do not always possess. Belinsky said that Turgenev “came to the people from a side from which no one had ever approached them before.”

The “golden heart” of the people is revealed by Turgenev in these stories. It is known that the art of a people is its soul. Strong, daring, passionate, it just came out in Yakov’s singing.

Listen to the text and determine its theme and main idea.

- Reading text

- Determining the theme and main idea.

- Vocabulary work (interpretation of words)

- Topic – description of Yakov’s singing (Jacob’s performance of the song). Thought - in the life of ordinary people there are such sublime moments that cleanse the soul;

True art unites and purifies people, regardless of class.

3. Illustration by Anatoly Belyukin:

What moment is depicted? (Jacob singing)

Who's in the foreground? (the singer himself)

What do the pose, face, look say? (they say that he forgot about everyone and gave himself up to singing).

Who do we see behind him on a dark background? (listeners)

Is the mass of people homogeneous? (different classes)

What do people's faces have in common? (frozen, concentrating, worried, pondering the meaning)

Does the illustration emphasize main idea text? (yes, all people are united by true art).

1. Interpretation of words.

Do you understand everything in this text?

How do you understand these words:

Flicker - glow faintly with fluctuating light;

Cracked - trembling, rattling;

Intoxication is the state of someone who enjoys, revels in something, delight.

- Text analysis

Style? (art)

Prove it.

The goal is to influence listeners with artistic words.

Belonging to works of Russian literature.

Syntax – common sentences, often SSP and SPP.

Vocabulary – many different means of language.

Type? (description of actions)

What parts is the text describing the actions divided into?

- Preparation (for singing)

- Execution (execution)

- Evaluation (listeners' feelings)

Plan. Let's try to find and title these parts.

- Yakov is getting ready to sing.

- “A mournful song poured out...”

- What does the Russian soul sound like?

- “The song flowed and developed...”

Image media.

1.-What verbs and in what order were used by Turgenev to show how the tension grew?

What other means of language were found in this part?

Pay attention to how the comparative phrase is written (commas)

- What means of language does the author use when talking about the growing sounds of the voice (First short adjectives, then full ones and turns into a metaphor: “A mournful song poured out”)

Pay attention to the syntax. Why do you think the author now chooses not individual short sentences, but uses complex and complex sentences, with different figures of speech. (Show the continuity of the process)

Punctuation marks.

1 ave. – seemed – introductory word and comparative phrase

2 ave. – comparative phrase, participial phrase

3 ave. – direct speech

Is it possible to split?

Of course, to make it easier to record (let's try)

- Speaking about Jacob's voice, he uses epithets and homogeneous subjects (how many things it contains!). Speaking about the soul, again a series of epithets, verbs and ends with a metaphor.

- Everything consists of metaphors that describe actions. In the third paragraph - non-union proposal, SSP and SPP are a complex syntactic whole. In the last paragraph the introductory word appears again - apparently.

- Vocabulary work.

Uneven, from somewhere, from afar, wavering, eerie, sweet, cracked, painful, genuine, useless, rapturously, fascinatingly carefree

- Repeated reading aloud.

- Working on a draft.

Jacob's Singing

Yakov paused, looked around and covered himself with his hand... When Yakov finally opened his face, it was pale, like a dead man’s, his eyes barely flickered through his lowered eyelashes. He took a deep breath and sang...

The first sound of his voice was weak and uneven and did not seem to come from his chest, but came from somewhere far away, as if it had accidentally flown into the room. This first sound was followed by another, more solid and drawn-out, but still apparently trembling, like a string, when, suddenly ringing under a strong finger, it vibrates with a final, quickly fading vibration, followed by a second or third, and, gradually heating up and expanding, poured mournful song. “There was more than one path in the field,” he sang, and we all felt sweet and terrified.

I admit, I have rarely heard such a voice: it was slightly broken and rang as if cracked; at first he even felt something painful, but there was also genuine deep passion, youth, strength, weakness, and some kind of fascinatingly carefree, sad grief. The Russian, truthful, ardent soul sounded and breathed in him, and just grabbed you by the heart, grabbed you right by its Russian strings.

The song grew and spread. Yakov, apparently, was overcome by ecstasy; he was no longer timid, he gave himself entirely to his happiness, his voice constantly grew stronger, hardened and expanded.

The small village of Kolotovka, which once belonged to a landowner, nicknamed Stryganikha in the neighborhood for her dashing and lively disposition (her real name remains unknown), and now owned by some St. Petersburg German, lies on the slope of a bare hill, cut from top to bottom by a terrible ravine, which, gaping like an abyss, winding, dug up and washed out, in the very middle of the street and more than the river - at least you can build a bridge across the river - separating both sides of the poor village. Several skinny willow trees timidly descend along its sandy sides; at the very bottom, dry and yellow as copper, lie huge slabs of clay stone. It’s a gloomy look, there’s nothing to say, but meanwhile all the surrounding residents know the road to Kolotovka well: they go there willingly and often. At the very head of the ravine, a few steps from the point where it begins with a narrow crack, there is a small quadrangular hut, standing alone, separate from the others. It is thatched, with a chimney; one window, like a watchful eye, faces the ravine and on winter evenings, illuminated from the inside, is visible far away in the dim fog of frost and twinkles as a guiding star to more than one passing peasant. There is a blue board nailed above the door of the hut: this hut is a tavern, nicknamed “Pritynny”. In this tavern, wine is probably not sold cheaper than the stated price, but it is visited much more diligently than all the surrounding establishments of the same kind. The reason for this is the kisser Nikolai Ivanovich. Nikolai Ivanovich - once a slender, curly and ruddy guy, now an unusually fat, already graying man with a swollen face, slyly good-natured eyes and a fat forehead, tied with wrinkles like threads - has been living in Kolotovka for more than twenty years. Nikolai Ivanovich is a quick and quick-witted man, like most of the kissers. Not being particularly polite or talkative, he has the gift of attracting and retaining guests who find it somehow fun to sit in front of his counter, under the calm and friendly, although watchful gaze of the phlegmatic owner. He has a lot of common sense; he is well acquainted with the life of a landowner, a peasant, and a bourgeois; in difficult cases, he could give intelligent advice, but, as a cautious and selfish person, he prefers to remain on the sidelines and, perhaps, with distant hints, as if without any intention, leads his visitors - and even his beloved visitors - to the path of truth. He knows a lot about everything that is important or interesting for a Russian person: horses and cattle, timber, bricks, dishes, red goods and leather goods, songs and dances. When he does not have a visit, he usually sits like a sack on the ground in front of the door of his hut, with his thin legs tucked under him, and exchanges affectionate words with all passers-by. He has seen a lot in his life, has outlived dozens of small nobles who came to him for “purified” things, knows everything that is going on a hundred miles around, and never blurts out, does not even show that he knows something that he does not the most perceptive police officer suspects. Know that he is silent, but chuckles, and moves his glasses. His neighbors respect him: civilian General Shcherepetenko, the first-ranking owner in the district, bows condescendingly to him every time he passes by his house. Nikolai Ivanovich is a man of influence: he forced a famous horse thief to return a horse that he had taken from the yard of one of his friends, brought some sense to the peasants of a neighboring village who did not want to accept a new manager, etc. However, one should not think that he did this out of love for justice, out of zeal for others - no! He simply tries to prevent everything that could somehow disturb his peace of mind. Nikolai Ivanovich is married and has children. His wife, a lively, sharp-nosed, quick-eyed bourgeois, has recently also become somewhat heavier in body, like her husband. He relies on her for everything, and she has the money under the key. Screaming drunkards are afraid of her; she doesn’t like them: there is little benefit from them, but there is a lot of noise; silent, gloomy ones are more to her heart. Nikolai Ivanovich's children are still small; the first ones all died, but the remaining ones took after their parents: it’s fun to look at the smart faces of these healthy kids. It was an unbearably hot July day when I, slowly moving my legs, together with my dog, climbed along the Kolotovsky ravine in the direction of the Prytynny tavern. The sun flared up in the sky, as if becoming fierce; it steamed and burned relentlessly; the air was completely saturated with stifling dust. Glossy rooks and crows, with their noses open, looked pitifully at those passing by, as if asking for their fate; Only the sparrows did not grieve and, fluffing their feathers, chirped and fought even more furiously over the fences, took off in unison from the dusty road, and hovered like gray clouds over the green hemp fields. Thirst tormented me. There was no water nearby: in Kolotovka, as in many other steppe villages, the men, lacking keys and wells, drink some kind of liquid mud from the pond... But who would call this disgusting swill water? I wanted to ask Nikolai Ivanovich for a glass of beer or kvass. Frankly, at no time of the year does Kolotovka present a pleasant sight; but it arouses a particularly sad feeling when the sparkling July sun with its inexorable rays floods the brown half-swept roofs of houses, and this deep ravine, and the scorched, dusty pasture along which thin, long-legged hens hopelessly wander, and the gray aspen frame with holes instead of windows, the remnant of the former manor's house, all around overgrown with nettles, weeds and wormwood, and covered with goose down, black, like a hot pond, with a border of half-dried mud and a dam knocked to one side, near which, on the finely trampled, ash-like ground, sheep, barely breathing and sneezing from the heat , they sadly crowd together and with sad patience bow their heads as low as possible, as if waiting for this unbearable heat to finally pass. With tired steps I approached Nikolai Ivanovich’s home, arousing, as usual, amazement in the children, reaching the point of tense, meaningless contemplation, indignation in the dogs, expressed by barking so hoarse and angry that it seemed that their entire insides were being torn off, and They themselves were coughing and choking when suddenly a tall man appeared on the threshold of the tavern, without a hat, in a frieze overcoat, belted low with a blue sash. In appearance he seemed like a courtyard; Thick gray hair rose in disarray over his dry and wrinkled face. He was calling to someone, hastily moving his arms, which apparently were swinging much further than he himself wanted. It was noticeable that he had already had a drink. - Go, go! - he babbled, raising his thick eyebrows with effort, - go, Morgach, go! How are you, brother, crawling, really? This is not good, brother. They are waiting for you here, and here you are crawling... Go. “Well, I’m coming, I’m coming,” a rattling voice was heard, and from behind the hut to the right a short, fat and lame man appeared. He was wearing a rather neat cloth jacket, threaded onto one sleeve; a tall, pointed hat, pulled straight down over his eyebrows, gave his round, plump face a sly and mocking expression. His small yellow eyes kept darting around, a restrained, tense smile never left his thin lips, and his nose, sharp and long, impudently pushed forward like a steering wheel. “I’m coming, my dear,” he continued, hobbling in the direction of the drinking establishment, “why are you calling me?.. Who’s waiting for me?” - Why am I calling you? - said the man in the frieze overcoat reproachfully. - What a wonderful little brother you are, Morgach: they call you to the tavern, and you still ask why. And all the good people are waiting for you: Turk-Yashka, and Wild Master, and the clerk from Zhizdra. Yashka and the rower made a bet: they set an octagon of beer - whoever defeats who will sing better, that is... you understand? - Will Yashka sing? - the man nicknamed Morgach said with liveliness. - And you’re not lying, Stupid? “I’m not lying,” answered Stunned with dignity, “but you’re lying.” Therefore, he will sing, if you bet, you are such a ladybug, you are such a rogue, Blink! “Well, let’s go, simplicity,” Morgach objected. “Well, at least kiss me, my soul,” babbled Stunned, opening his arms wide. “Look, Ezop is effeminate,” Morgach answered contemptuously, pushing him away with his elbow, and both, bending down, entered the low door. The conversation I heard greatly aroused my curiosity. More than once I had heard rumors about Yashka the Turk as the best singer in the area, and suddenly I had the opportunity to hear him in competition with another master. I doubled my steps and entered the establishment. Probably not many of my readers have had the opportunity to look into village taverns: but our brother, the hunter, where he does not go! Their design is extremely simple. They usually consist of a dark entryway and a white hut, divided in two by a partition, behind which no visitor has the right to enter. In this partition, above the wide oak table, a large longitudinal hole was made. Wine is sold on this table, or stand. Sealed damasks different sizes They stand side by side on shelves, directly opposite the hole. In the front part of the hut, provided to visitors, there are benches, two or three empty barrels, and a corner table. Village taverns for the most part are quite dark, and you will almost never see on their log walls any brightly colored popular prints, which few huts can do without. When I entered the Prytynny tavern, a fairly large crowd had already gathered there. Behind the counter, as usual, almost the entire width of the opening, stood Nikolai Ivanovich, in a motley cotton shirt, and, with a lazy grin on his plump cheeks, poured with his full and white hand two glasses of wine to his friends who came in, Blink and Stunned; and behind him, in the corner, near the window, his sharp-eyed wife could be seen. In the middle of the room stood Yashka the Turk, a thin and slender man of about twenty-three, dressed in a long-skirted blue nankeen caftan. He looked like a dashing factory fellow and, it seemed, could not boast of excellent health. His sunken cheeks, large restless gray eyes, a straight nose with thin, mobile nostrils, a white sloping forehead with light brown curls thrown back, large but beautiful, expressive lips - his whole face revealed an impressionable and passionate man. He was in great excitement: he was blinking his eyes, breathing unevenly, his hands were trembling as if in a fever - and he definitely had a fever, that alarming, sudden fever that is so familiar to all people who speak or sing before a meeting. Next to him stood a man of about forty, broad-shouldered, high-cheeked, with a low forehead, narrow Tatar eyes, a short and flat nose, a quadrangular chin and black shiny hair, stiff as stubble. The expression of his dark, leaden face, especially his pale lips, could be called almost ferocious if it were not so calm and thoughtful. He hardly moved and only slowly looked around, like a bull from under a yoke. He was dressed in some kind of shabby frock coat with smooth copper buttons; an old black silk scarf wrapped around his huge neck. His name was Wild Master. Sitting directly opposite him, on a bench under the icons, was Yashka’s rival, a soldier from Zhizdra. He was a short, stocky man of about thirty, pockmarked and curly-haired, with a blunt upturned nose, lively brown eyes and a thin beard. He looked around briskly, tucked his arms under him, carelessly chatted and tapped his feet, shod in smart boots with trim. He was wearing a new thin overcoat made of gray cloth with a corduroy collar, from which the edge of a scarlet shirt, tightly buttoned around the throat, was sharply separated. In the opposite corner, to the right of the door, a peasant in a narrow, worn-out retinue, with a huge hole in his shoulder, was sitting at a table. Sunlight streamed in a liquid yellowish stream through the dusty glass of two small windows and, it seemed, could not overcome the usual darkness of the room: all objects were sparingly illuminated, as if in spots. But it was almost cool inside, and the feeling of stuffiness and heat, like a burden, fell from my shoulders as soon as I crossed the threshold. My arrival—I could notice it—at first somewhat embarrassed Nikolai Ivanovich’s guests; but, seeing that he bowed to me as if he were a familiar person, they calmed down and no longer paid attention to me. I asked myself a beer and sat down in a corner, next to a peasant in a tattered retinue. - Well! - Stunned suddenly cried out, drinking a glass of wine in spirit and accompanying his exclamation with those strange waving of his hands, without which he, apparently, did not utter a single word. - What else are you waiting for? Start like this. A? Yasha?.. “Start, start,” Nikolai Ivanovich chimed in approvingly. “Let’s get started,” the clerk said coolly and with a self-confident smile, “I’m ready.” “And I’m ready,” Yakov said with excitement. “Well, start, guys, start,” Morgach squeaked. But, despite the unanimously expressed desire, no one began; the rower didn’t even rise from his bench—everyone seemed to be waiting for something. - Start! - Wild Master said gloomily and sharply. Yakov shuddered. The clerk stood up, pulled down his sash and cleared his throat. - Who should start? - he asked in a slightly changed voice to the Wild Master, who continued to stand motionless in the middle of the room, with his thick legs spread wide and his powerful hands thrust almost to the elbows into the pockets of his trousers. “To you, to you, row guy,” the Stunned Man babbled, “to you, brother.” The Wild Master looked at him from under his brows. The stunner squeaked weakly, hesitated, looked somewhere at the ceiling, shrugged his shoulders and fell silent. “Toss the lot,” said the Wild Master with emphasis, “up to an eighth on the stand.” Nikolai Ivanovich bent down, grunting, and took out an octopus from the floor and put it on the table. The Wild Master looked at Yakov and said: “Well!” Yakov dug into his pockets, took out a penny and marked it with his teeth. The clerk took out a new leather wallet from under the skirt of his caftan, slowly unraveled the lace and, pouring a lot of change into his hand, chose a brand new penny. The stunner presented his worn-out cap with a broken and detached visor; Yakov threw his penny at him, and the clerk threw his. “You choose,” said the Wild Master, turning to Morgach. The blinker grinned smugly, took the cap in both hands and began to shake it. Instantly, deep silence reigned: the pennies clinked faintly, hitting each other. I looked around carefully: all the faces expressed tense expectation; The Wild Master himself narrowed his eyes; my neighbor, a little man in a tattered scroll, and he even craned his neck with curiosity. The morgach put his hand into his cap and took out rows of pennies; everyone sighed. Yakov blushed, and the clerk ran his hand through his hair. “I told you what,” exclaimed Stunned, “I told you so.” - Well, well, don’t “circus”! - the Wild Master remarked contemptuously. “Begin,” he continued, shaking his head at the clerk. - What song should I sing? - asked the clerk, getting excited. “Whatever you want,” answered Morgach. - Sing whatever you want. “Of course, whichever one you want,” added Nikolai Ivanovich, slowly folding his hands on his chest. - There is no decree for you in this. Sing whatever you want; just sing well; and then we will decide according to our conscience. “Of course, in good faith,” said Stunned and licked the edge of the empty glass. “Let me clear my throat a little, brothers,” said the clerk, running his fingers along the collar of his caftan. - Well, well, don’t be idle - get started! - Wild Master decided and looked down. The rower thought for a moment, shook his head and stepped forward. Yakov glared at him... But before I begin to describe the competition itself, I think it would not be superfluous to say a few words about each of the characters in my story. The life of some of them was already known to me when I met them in the Prytynny tavern; I collected information about others later. Let's start with Obalduya. This man's real name was Evgraf Ivanov; but no one in the whole neighborhood called him anything other than Stupid, and he himself called himself by the same nickname: it stuck so well to him. And indeed, it suited his insignificant, eternally anxious features perfectly. He was a debauched, single courtyard man, whom his own masters had abandoned long ago and who, having no position and not receiving a penny of salary, nevertheless found a way every day to carouse at someone else’s expense. He had many acquaintances who gave him wine and tea, without knowing why, because not only was he not funny in society, but, on the contrary, he bored everyone with his meaningless chatter, unbearable obsession, feverish body movements and incessant unnatural laughter. He could neither sing nor dance; I’ve never said anything smart, or even worthwhile, in my life: I’ve always been playing around and lying about everything - straight up Stupid! And yet, not a single drinking party for forty miles around was complete without his lanky figure hovering right there among the guests - they had become so accustomed to him and tolerated his presence as a necessary evil. True, they treated him with contempt, but only the Wild Master knew how to tame his absurd impulses. Blinker did not at all resemble the Stunner. The name Morgach also suited him, although he did not blink his eyes more than other people; It’s a well-known fact: the Russian people are nicknamed master. Despite my efforts to find out in more detail the past of this man, in his life there remained for me - and, probably, for many others - dark spots, places, as the scribes put it, covered in the deep darkness of the unknown. I only learned that he had once been a coachman for an old childless lady, ran away with the three horses entrusted to him, disappeared for a whole year and, apparently having become convinced in practice of the disadvantages and disasters of a wandering life, returned on his own, but already lame, threw himself at his feet. mistress and, over the course of several years, having made amends for his crime with exemplary behavior, he gradually came into her favor, finally earned her full power of attorney, became a clerk, and after the death of the lady, no one knows how, he was released, registered as a bourgeois, and began renting Bakshi's neighbors, got rich and now lives happily ever after. This is an experienced person, on his own, not evil and not kind, but more calculating; This is a grated kalach who knows people and knows how to use them. He is careful and at the same time enterprising, like a fox; talkative, like an old woman, and never lets slip, but forces everyone else to speak out; however, he does not pretend to be a simpleton, as other cunning people of the same dozen do, and it would be difficult for him to pretend: I have never seen more penetrating and intelligent eyes than his tiny, crafty “peepers.” They never just look - they look and spy on everything. A blinker sometimes spends whole weeks thinking about some apparently simple undertaking, and then suddenly decides on a desperately bold undertaking; It seems like he’s about to break his head... you look - everything worked out, everything went like clockwork. He is happy and believes in his happiness, believes in signs. He is generally very superstitious. They don’t like him because he doesn’t care about anyone, but they respect him. His entire family consists of one son, in whom he dotes and who, raised by such a father, will probably go far. “And Little Blinker took after his father,” the old people are already saying about him in low tones, sitting on the rubble and talking among themselves on summer evenings; and everyone understands what this means and no longer adds a word. There is no need to dwell at length on Yakov the Turk and the rower. Yakov, nicknamed the Turk, because he really was descended from a captive Turkish woman, was by heart an artist in every sense of the word, and by rank a scooper at a merchant’s paper mill; As for the contractor, whose fate, I admit, remained unknown to me, he seemed to me a resourceful and lively city tradesman. But it’s worth talking about the Wild Master in a little more detail. The first impression that the sight of this man made on you was a feeling of some rough, heavy, but irresistible strength. He was built clumsily, “knocked down,” as we say, but he reeked of indestructible health, and - a strange thing - his bearish figure was not devoid of some kind of peculiar grace, which perhaps came from a completely calm confidence in own power. It was difficult to decide at first what class this Hercules belonged to; he did not look like a serf, or a tradesman, or an impoverished retired clerk, or a small, bankrupt nobleman - a huntsman and a fighter: he was certainly on his own. Nobody knew where he came from in our district; it was rumored that he was descended from members of the same palace and seemed to have been in the service somewhere before; but they didn’t know anything positive about it; and from whom was it possible to find out - not from himself: there was no more silent and gloomy person. Also, no one could positively say what he lived by; he did not engage in any craft, did not travel to anyone, knew almost no one, but he had money; True, they were small, but they were found. He behaved not only modestly - there was nothing modest about him at all - but quietly; he lived as if he didn’t notice anyone around him and absolutely didn’t need anyone. Wild Master (that was his nickname; his real name was Perevlesov) enjoyed enormous influence throughout the entire district; they obeyed him immediately and willingly, although he not only had no right to order anyone, but he himself did not even express the slightest claim to the obedience of the people whom he chanced to encounter. He spoke - they obeyed him; strength will always take its toll. He hardly drank wine, did not date women, and passionately loved singing. There was a lot of mystery about this man; it seemed as if some enormous forces rested sullenly within him, as if knowing that once they had risen, that once they had broken free, they must destroy themselves and everything they touched; and I am sorely mistaken if such an explosion had not already happened in this man’s life, if he, taught by experience and having barely escaped death, did not now inexorably hold himself under a tight rein. What especially struck me in him was the mixture of some kind of innate, natural ferocity and the same innate nobility - a mixture that I had not encountered in anyone else. So, the rower stepped forward, closed his eyes halfway and sang in the highest falsetto. His voice was quite pleasant and sweet, although somewhat hoarse; he played and wiggled this voice like a top, constantly poured and shimmered from top to bottom and constantly returned to the upper notes, which he sustained and pulled out with special diligence, fell silent and then suddenly picked up the previous tune with some kind of rollicking, arrogant prowess. His transitions were sometimes quite bold, sometimes quite funny: to a connoisseur they would give a lot of pleasure; a German would be indignant at them. It was the Russian tenore di grazia, tenor léger. He sang a cheerful, dancing song, the words of which, as far as I could catch through the endless decorations, added consonants and exclamations, were as follows:

I will open it, young and young,

The earth is small;

I will sow, young and young,

Tsvetika alenka.

The small village of Kolotovka lies on the slope of a bare hill, dissected by a deep ravine that winds through the very middle of the street. A few steps from the beginning of the ravine there is a small quadrangular hut, covered with straw. This is the “Pritynny” tavern. It is visited much more willingly than other establishments, and the reason for this is the kisser Nikolai Ivanovich. This unusually fat, gray-haired man with a swollen face and slyly good-natured eyes has been living in Kolotovka for more than 20 years. Not being particularly polite or talkative, he has the gift of attracting guests and knows a lot about everything that is interesting to a Russian person. He knows about everything that happens in the area, but he never spills the beans.

Nikolai Ivanovich enjoys respect and influence among his neighbors. He is married and has children. His wife is a lively, sharp-nosed, quick-eyed bourgeois, Nikolai Ivanovich relies on her for everything, and the loud-mouthed drunkards are afraid of her. Nikolai Ivanovich's children took after their parents - smart and healthy guys.

It was a hot July day when, tormented by thirst, I approached the Pritynny tavern. Suddenly, a tall, gray-haired man appeared on the threshold of the tavern and began to call someone, waving his hands. A short, fat and lame man with a sly expression on his face, nicknamed Morgach, responded to him. From the conversation between Morgach and his friend Obolduy, I understood that a singing competition was being started in the tavern. The best singer in the area, Yashka Turok, will show his skills.

Quite a lot of people had already gathered in the tavern, including Yashka, a thin and slender man of about 23 years old with large gray eyes and light brown curls. Standing next to him was a broad-shouldered man of about 40 with black shiny hair and a fierce, thoughtful expression on his Tatar face. His name was Wild Master. Opposite him sat Yashka's rival - a clerk from Zhizdra, a stocky, short man of about 30, pockmarked and curly-haired, with a blunt nose, brown eyes and a thin beard. The Wild Master was in charge of the action.

Before describing the competition, I want to say a few words about those gathered in the tavern. Evgraf Ivanov, or Stunned, was a bachelor on a spree. He could neither sing nor dance, but not a single drinking party was complete without him - his presence was endured as a necessary evil. Morgach's past was unclear, they only knew that he was a coachman for a lady, became a clerk, was released and became rich. This is an experienced person with his own mind, neither good nor evil. His entire family consists of a son who took after his father. Yakov, who was descended from a captured Turkish woman, was an artist at heart, and by rank he was a scooper at a paper factory. No one knew where the Wild Master (Perevlesov) came from and how he lived. This gloomy man lived without needing anyone and enjoyed enormous influence. He did not drink wine, did not date women, and was passionate about singing.

The clerk was the first to sing. He sang a dance song with endless decorations and transitions, which brought a smile from the Wild Master and the stormy approval of the rest of the listeners. Yakov began with excitement. In his voice there was deep passion, and youth, and strength, and sweetness, and fascinatingly carefree, sad grief. The Russian soul sounded in him and grabbed his heart. Tears appeared in everyone's eyes. The rower himself admitted defeat.

I left the tavern, so as not to spoil the impression, got to the hayloft and fell fast asleep. In the evening, when I woke up, the tavern was already celebrating Yashka’s victory with might and main. I turned away and began to walk down the hill on which Kolotovka lies.

“The consequences of the industrial revolution in England” - Stages of the industrial revolution. Significant capital accumulation created the conditions for the development of the financial and credit system. The Industrial Revolution began in light industry. In 1784 J. Watt created steam engine. Export of English cotton goods. Contents and consequences of the industrial revolution for the world economy.

“Certification of teaching staff” - First type – Certification of the teacher’s suitability for the position held (clauses 17-24 of the Certification Procedure). Based on the results of the certification, the AC makes a decision on whether he or she is appropriate for the position held (the employee’s position is indicated); does not correspond to the position held (the employee’s position is indicated). Registration of certification results.

"Skeleton" - Walks. What is a skeleton for? Conclusions. Target. The structure of the human skeleton. Reliable support and protection of the human body. First aid. How to grow tall and slender. Injuries to bones and joints. Rules for maintaining correct posture. How to sit and walk correctly. What properties do bones have?

“Asexual reproduction” - Interdisciplinary connections: botany - zoology - genetics. Topic: “Asexual reproduction.” Lesson conclusions: During asexual reproduction, new individuals are formed from one or more cells of the mother’s body through mitotic divisions. Problematic question of the lesson: Why does asexual reproduction ensure the constancy of the set of chromosomes over generations?

“Prince Yaroslav the Wise” - Yaroslav Vladimirovich the Wise. Kyiv throne. Yaroslav the Wise. Domestic policy Yaroslav. The Pechenegs attacked Rus'. Death of Yaroslav. Yaroslav. Grand Duke of Kyiv. Monument to Yaroslav. Brothers Yaroslav and Mstislav. Reading Russian Truth to the people. Merits of Yaroslav the Wise. Kyiv under Yaroslav. Enlightener of Rus'.

“Lakes of the Russian Plain” - Average area – 1120 sq. km. Lake Peipus. Thirty-two rivers flow into Ladoga. Pskov Lake Peipus. Level fluctuations up to 8 m (minimum - in March, maximum - in May). The ice lasts from November to April. Views of Lake Ladoga. The northern section of Lake Onega is the deepest. Ladoga has a very wide variety of fish species.

Yashka the Turk (Yakov) is one of the heroes of I. S. Turgenev’s story “The Singers” from the series “Notes of a Hunter.” Yakov's mother was a captive Turkish woman, which is why he got his nickname. Everyone in the area knew that he was the best singer in the area. He looked to be 23 years old, slender, thin, with large gray eyes and light brown curls. His face was impressionable and passionate. An artist at heart, in fact, he worked as a scooper in a paper mill for a merchant. One July day, in the “Prytynny” tavern in the village of Kotlovka, he competed in singing with a clerk and Zhizdra. Yashka put on his blue caftan and looked like a dashing factory fellow in it. He was very worried.

The rower sang first. His song was a dance song with endless decorations and transitions. His voice was sweet and pleasant. He tried his best to please the assembled audience. When he finished singing, everyone was sure that victory belonged to the dodgy rower. It was Jacob's turn. He first covered himself with his hand, then took a deep breath and began to sing. Everyone around froze. The narrator was amazed by his voice, so ringing, hysterical and full of sad sorrow. His voice touched everyone's soul. Many had tears rolling down their eyes. Even the Wild Master could not resist and shed a stingy tear. Unlike the clerk, Yakov did not try to please everyone. He simply sang with all his soul, giving himself entirely to his happiness. When he finished singing, the rower himself realized that he had lost. And in the evening in the tavern everyone celebrated Yashkin’s victory.